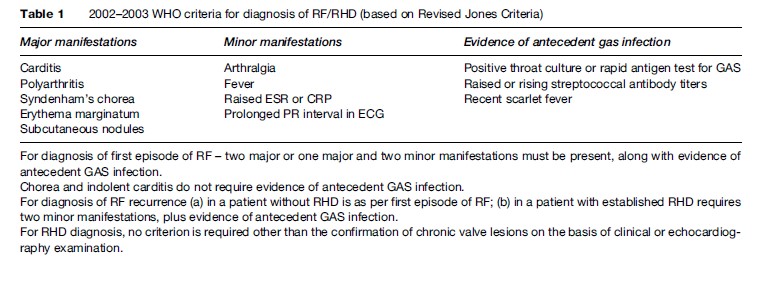

The clinical features suggestive of RF were first established in 1944 by T. Ducket Jones ( Jones, 1944), and thereafter updated and modified occasionally to increase the specificity for diagnosis of RF (Table 1). Carditis is the single most important manifestation of the RF and its presence determines the course of disease, its duration, and the intensity of prophylaxis. The diagnosis of carditis is based on clinical examination, i.e., presence of significant regurgitant murmur, pericardial rub, or cardiomegaly with congestive heart failure. In case of recurrence of RF, a new murmur or a change in the character of a previously documented murmur, pericardial rub, or an increase in cardiac size with demonstration of valvular damage or involvement is required. The physician’s clinical judgment is of prime importance in diagnosis of carditis, and it can be confirmed by echocardiography, if facilities are available. Echocardiography can provide early evidence of valve involvement and confirms the rheumatic or nonrheumatic causes of murmur or valvular regurgitation. It has the definite advantage of diagnosing valvulitis in an otherwise clinically normal heart, and helps in deciding on duration of secondary prophylaxis. According to a recent study of RHD prevalence in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the comprehensive echocardiographic screening identified approximately ten times as many children with RHD as were identified by the traditional strategy of clinical screening followed by echocardiographic confirmation (Marijion et al., 2007). This observation has an important implication for case findings, delivery of effective primary and secondary prevention, and appropriate planning for scarce health resource utilization. There is a logistic problem of routine use of echocardiography in RF diagnosis because of overdiagnosis of physiologic valvular regurgitation as pathological, the inability to diagnose subclinical carditis in patients with RF recurrence, and the lack of an echocardiography facility, affordability, or expertise at the community level. As the sizable percentage of children who have subclinical carditis are at risk for RF recurrence and progression to RHD, it is not acceptable to leave them without further management in view of nonavailability of echocardiographic screening. Further research is needed to define models of echocardiographic screening that are practical, affordable, and widely applicable in developing countries.

Evidence of antecedent GAS infection is required for the confirmation of an RF episode (Table 1). Only 11% of acute RF patients are found to have positive throat swab culture for GAS, as the rest of patients’ immune systems eradicate GAS during the latent period between pharyngitis and RF (Dajani, 1991). The commercially available rapid antigen test for diagnosing GAS pharyngitis has a high specificity, up to 99%, but sensitivity is only 66% in the clinical setting, requiring a backup throat swab culture in patients with negative rapid antigen test (Limbergen et al., 2006). Both positive throat swab culture and rapid antigen test do not differentiate between the recent infections leading to RF and the chronic carrier state of the organism. On the other hand, the elevated or rising ASO titers are more informative and reliable for recent GAS infection.

Treatment

Treatment of acute RF includes antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and supportive treatment. Benzathine penicillin G, 1.2 million units in a single intramuscular injection or oral penicillin V/erythromycin for 10 days must be given for GAS infection empirically. Anti-inflammatory drugs include aspirin for severe arthralgia or arthritis and steroids for significant carditis must be added. Supportive treatment includes bed rest, anti-heart failure and antipyretic drugs. Depending upon type and severity of the valvular lesion, RHD patients require long-term treatment for heart failure, atrial fibrillation, thromboembolism, and infective endocarditis as well as RF recurrence prophylaxis and interventions such as valvuloplasty or valve replacement surgery.

Prevention Of RF

Primary Prevention

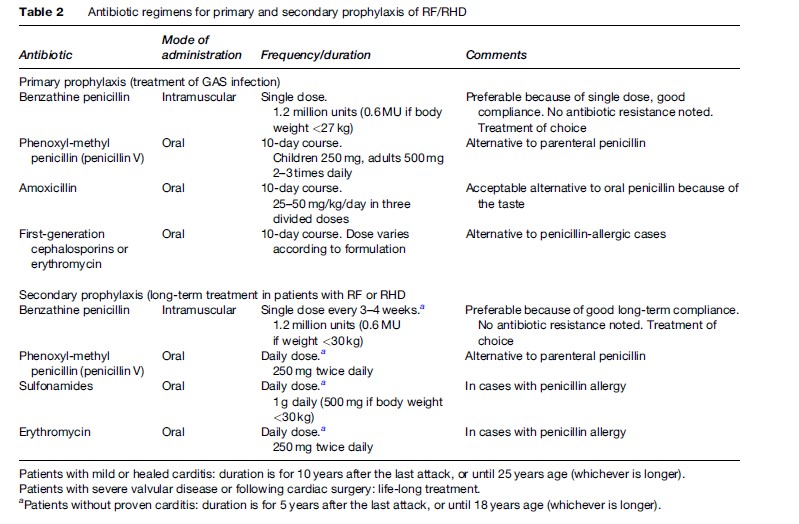

The aim of primary prevention is to prevent the first attack of RF by identifying and treating all the suspected or proven streptococcal pharyngitis cases in children aged 3–15 years age. Antibiotic treatment should preferably be started within 9 days of a sore throat for effective prevention of RF development. In endemic areas, all symptomatic sore throat cases with clinical suspicion of GAS infection should be treated with antibiotics. Throat swab culture or rapid antigen test for GAS should be done if laboratory services are available; however, in the absence of these services, the antibiotics should not be delayed or avoided. Table 2 describes the antibiotic treatment for GAS throat infection. The rheumatic vaccine in the near future might be a tool for prevention of streptococcal pharyngitis and RF recurrence. Progress is continuing in development of a vaccine against M serotypes, streptococcal fibronectin binding protein-1 (sfb1), and streptococcal C5a peptidase (SCPA). However, there are practical problems in developing a vaccine such as rapid and complete change of GAS serotypes in the community, presence of asymptomatic GAS carriers, ability of streptococci to infect the host after a prior infection by a different M serotype strain, cross-reactivity of M protein vaccine with human tissues, and the cost effectiveness of the vaccine, especially in developing countries with high prevalence of GAS pharyngitis and carrier rates.

Secondary Prevention

The aim of secondary prevention is to prevent the recurrence of RF and further damage of cardiac valves in proven cases of RF/RHD. The individual who has suffered from a prior RF episode is more prone to have GAS pharyngitis and RF recurrences. The secondary prevention strategy is more practical and cost-effective than the primary prevention, especially in developing countries with limited health resources. Table 2 describes the treatment regimen for secondary prevention. Infective endocarditis is another complication with significant morbidity and mortality in patients with RHD or prosthetic valves. The routine infective endocarditis prophylaxis prior to any surgical or dental procedure is recommended in all patients with RHD.

Community-Based Measures For Prevention Of RF/RHD

Despite the appropriate primary and secondary preventive measures available for decades, the disease could not be controlled, especially in developing countries, because of social determinants such as housing, education, and poverty; health-care determinants such as access to primary health care, the scarcity of trained health-care workers, the logistics of drug supply and cost of medical treatment, and the availability of sophisticated cardiology and cardiac surgery services. It is important that the prevention and control programs to be started in the community should be cost-effective, integrated, and applicable with limited available health resources. The national programs should be planned with their objectives and approach adapted to local needs and circumstances, and they should be implemented through the existing infrastructure of the health-care and education system. There is also a need for regular surveillance of acute RF, RHD, and GAS pharyngitis in the community to provide useful information on the epidemiological trends of the disease. The national program should constitute the activities related with primary and secondary prevention, health education, and training of health-care workers.

Primary Prevention Activities

The primary prevention program is not cost-effective, particularly in endemic states, because only 10–20% of symptomatic sore throat is from GAS, one-third of all RF cases follow mild or almost asymptomatic pharyngitis, which might be missed, only less than 3% of these GAS pharyngitis evolve into RF, and approximately 60% of these RF cases continue to evolve to RHD. Also, because of limited health resources, the lack of penicillin, and populations unlikely to seek and adhere to treatment for sore throat, an alternative cost-effective strategy would be to intervene with high-risk groups. There is also a need for adequate microbiology laboratory support at peripheral, intermediate, and tertiary care levels for GAS infection identification, M subtyping, and serological investigations.

Secondary Prevention Activities

Secondary prevention is based on finding cases, referral, registration, active and passive surveillance, follow-up, and regular secondary prophylaxis of RHD patients. A local center in endemic areas should be established for referral and registration of RF/RHD patients, should be adequately equipped for laboratory tests related to RF and streptococcal pharyngitis, and should have health-care workers for medical care. The secondary prevention with penicillin prophylaxis is the most cost-effective strategy. Attention should be given for strict compliance of long-term penicillin prophylaxis in RF/RHD patients, as the defaulters are very frequent because of long-term therapy for years, painful injection, lack of health awareness and education, fear of penicillin allergy and anaphylaxis, the nonavailability of drugs, and social reasons. Strengthening diagnostic accuracy and curative services throughout the region must go hand in hand with preventive measures. Adequate infrastructures such as streptococcal diagnostic labs and echocardiography machines at the ground level with adequate expertise are essential. A lack of diagnostic and treatment facilities and the unaffordable cost of medical care add to the huge existing burden of RHD. The cost of surgery makes this option impractical for most patients. There is also a gross mismatch in the supply and demand ratio for cardiac surgery in developing countries. There are 1222 cardiac surgeries done per million population in North America, which is far more than the 25 surgeries in Asia and 18 surgeries in Africa. It is estimated that only 7% of needy patients undergo cardiac surgery in Asia, Africa, South America, and Russia. This is because of the nonavailability of infrastructure, expertise, unaffordable cost and the lack of medical insurance. Even following valve surgery, there is a need for long-term monitoring for anticoagulation treatment, infective endocarditis, bleeding and thrombotic complications, cost and availability of anti-heart failure and anticoagulant treatment in the community.